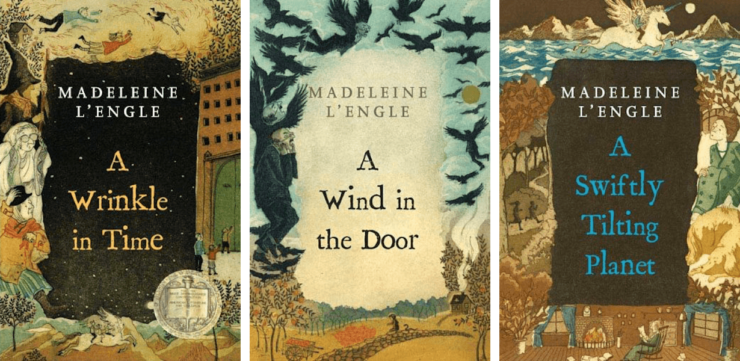

Madeleine L’Engle was my first sci-fi. Maybe also my first fantasy. I read her before Lewis, Tolkien, Adams, Bradbury. I was 11 when I read A Wrinkle in Time, and I quickly burned through all the rest of her YA, and I even dug into her contemplative journals a bit later, as I began to study religion more seriously in my late teens.

My favorite was A Swiftly Tilting Planet (I’m embarrassed to tell you how often I’ve mumbled St. Patrick’s Breastplate into whichever adult beverage I’m using as cheap anesthetic to keep the wolves from the door over this past year) but I read all of her books in pieces, creating a patchwork quilt of memories. I loved the opening of this one, a particular death scene in that one, an oblique sexual encounter in another. Bright red curtains with geometrical patterns, The Star-Watching Rock, hot Nephilim with purple hair—the usual stuff. But as I looked back over L’Engle’s oeuvre and I was struck, more than anything, by the sheer weirdness of her work.

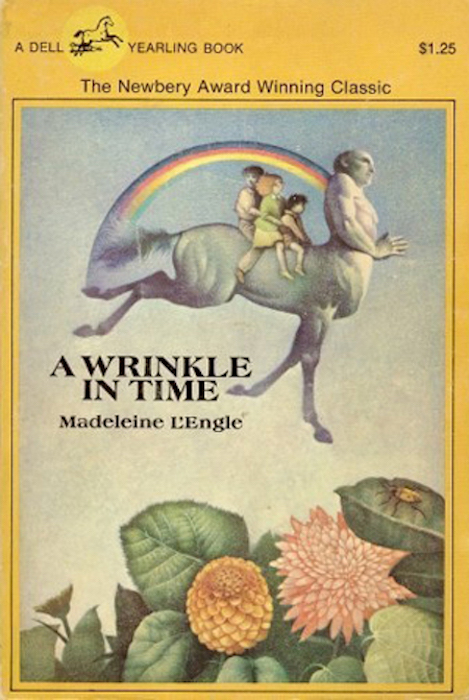

I only read Madeleine L’Engle for school. For years, I had stared warily at the cover for A Wrinkle in Time—this one—

—which for some reason terrified me. It was so unsettling, the combination of yellow and something about the centaur, but at the same time I was attracted to it. Every time I was in the YA section of a bookstore, I would visit it and dare myself to pick it up. And then it was an assigned book in 7th grade, and being a good nerd, I was still really invested in my grades, so I quickly dismissed two years of apprehension.

From the opening line, I was hooked. And then I kept reading, and A Wrinkle in Time quickly became one of those books that I read throughout one long night because I couldn’t put it down. I read it to pieces. And over the next year I got all the rest of L’Engle’s books with birthday and Christmas money. I remember being thrilled to see how all the characters fit together—I think this was the first time I’d read books that comprised a universe in this way. I’d read sequels, and was grudgingly accepting of the fact that Temple of Doom happened before Raiders, despite being made after (it really bugged me), but this? This was different. Characters crossed over into each other’s books! The staid, utterly realistic Austins knew about the Murrys! (And yes, this blew the timeline and complicated everything later, as Mari Ness points out in her reread, but for me it was such a giant moment of worldbuilding that I didn’t care. At least, not then.) Canon Tallis is an uncle-figure to both Polly and Vicky! Zachary Grey dates, like, half the women!

But here’s the key to L’Engle’s true brilliance and the reason she’s still beloved: She hops exuberantly through genres without ever explaining or apologizing. Either you can keep up, or you can find a new book. I still remember the feeling of exhilaration as I read her. The feeling that ideas were being stuffed into my brain faster than I could process them.

Right off the bat there’s Meg, a girl who is nothing like any other girl in YA that I’d read up to that point. Meg’s awesomeness has been lauded before, but I do want to point out: Meg in and of herself was a goddamn revolution. This wasn’t poetic, fanciful Anne or Emily, or tough pioneer girl Laura. Meg couldn’t be classified as the goody-two-shoes Wakefield twin, or the vamp; she never would have joined the Babysitters’ Club, or taken ballet classes, or sighed longingly over a horse. When we meet Meg she’s bespectacled, brace-faced, and deeply depressed. She’s unpopular. She has a shiner—not because a bully hit her, or a parent abused her, but because she launched herself at some older boys who mocked her little brother, and did enough damage that their parents complained. And after we know all this about her, then we learn that she’s a math nerd. And she remains prickly and awesome over the course of this book, and the next, and seemingly doesn’t soften until she’s a twenty-something with a baby on the way.

Meg’s plot is a fantasy version of a coming-of-age tale. Like a more realistic story, she has to tap into her own talents and hidden strengths in order to accomplish something great. But here’s where the first weirdness sets in: The thing she has to do is rescue her father…from another planet…using math and time travel. We begin in a gothic horror, in a creaky attic on a dark and stormy night. Then we’re in the mind of a troubled YA heroine. But then suddenly we’re in a cozy family story, complete with hot cocoa simmering on the stove and a loving dog whumping his tail on the kitchen floor. And then we learn that the YA heroine’s baby brother, the one she defended, is a super genius…who might be telepathic? How many genres even is that? A hurricane rages outside, a toddler can read minds, and, wait, there’s a weird-looking stranger at the door.

The book veers into pure SFF about a chapter in, tellingly, when Meg and new friend Calvin O’Keefe are discussing Meg’s father’s disappearance. The townspeople are united in their belief that Meg’s dad has run off with another woman, and Meg begins to cry until Calvin tells her she’s beautiful without her glasses (ugh, I know…). But it’s almost as though L’Engle is giving us this conventional, maudlin teenage moment just to undercut it. Because where in a normal YA book you’d get a first kiss, here we get three supernatural beings and the telepathic toddler showing up to announce that they’re all going on an interstellar quest to save Dr. Murry.

You know, like you do.

From there the book launches into L’Engle’s usual pace, throwing ideas around like confetti as she hurtles her readers through space. Along the way we visit a several new planets, briefly stop in a two-dimensional plane that nearly kills the children (while also providing a cute riff on Edwin A. Abbott’s Flatland), I finally got to meet the centaur I’d been so afraid of, only to learn that it was Mrs. Whatsit all along, and then learned the true meaning of fear on Camazotz—but I’ll come back to that in a sec.

In each of these we get the sense of fully-realized worlds with their own societies, and there’s every indication we’re only seeing a tiny sliver of the universe. By committing to the tessering concept, L’Engle takes the training wheels off her worldbuilding. We can just hop from world to world as easily as she hops between science and religion, sci-fi and realism.

In The Young Unicorns, she posits a nefarious group of people are running around Manhattan lobotomizing people with a laser…but this isn’t a government plot, or a gang, it’s a bishop and a doctor. And yes, it turns out that the bishop is an imposter, but L’Engle allows the idea that a religious leader has been attacking kids with a laser to hang out on the page for a shockingly long time. And then she gives us the twist that the two men are trying remove people’s capacity for evil (the book is firmly against this), which results in an Episcopal Canon arguing free will with a street gang. In The Arm of the Starfish, L’Engle gives us an international espionage plot that centers on a new form of medicine: using starfish DNA to help people re-grow injured limbs. We get adorable pony-sized unicorns in Many Waters, and a majestic unicorn in A Swiftly Tilting Planet. She gives us angels who used to be stars; angels who are snarky, shambling piles of wings and eyes; and angels with super gothy blue-and-purple wings. She makes it feel terrifyingly plausible that you might go for a walk in your backyard, and look up to realize that you’re 3,000 years in the past.

I should mention that not all of this craziness was necessarily great. She did have a tendency to equate “light” with good and “black” with evil. She also perpetuated a really odd Noble Savage/Celt/Druid thing, and also some of her books promote much more gender normativity than I’m comfortable with. I know some people have issues with House Like a Lotus, a realistic coming-of-age story starring Meg’s daughter Polly O’Keefe. Polly is going through an awkward adolescence in a tiny Southern town. Her only real friends are an elderly lesbian and a male med student in his twenties, and over the course of the book both of these characters make advances toward Polly that range form inappropriate to legally not-OK. For me, as a 12-year-old reading it, Lotus was one of the first matter-of-fact depictions of queerness I ever saw. What I took away from it was a very realistic depiction of small-minded homophobia; a loving, lifelong relationship between two women; and the idea that one of the women was capable of being a monster when she was drunk. What I took away, in other words, was a portrait of a complicated relationship, and a pair of people who were just as fucked up as all of their straight friends. It was pretty easy for me to take that and equate it with all the other complicated adult relationships I saw in life and in fiction, and to just file it away as a lesson not to mix liquor with painkillers.

But the weirdest thing of all is simply that L’Engle gave us a giant battle between GOOD and EVIL, showing us both the enormous stakes of interstellar war, and the tiny decisions that could tip the very balance of the universe. In each book, however, she’s very careful to show us kids could absolutely fight in those battles. From the opening of A Wrinkle in Time, mother lovingly looks at her daughter’s black eye to check how it’s healing, and chooses not to yell at Meg. Dr. Murry is under tremendous pressure, but she recognizes that Meg made a moral choice, and drew a line in the sand to stand up for her brother. That’s one way to fight. We see later that throwing poetry and mathematics at the enemy also works. That relying on love works. In The Wind in the Door, L’Engle gives us tiny sentient creatures called farandolae living within the cells of a dying boy. She shows us that the farandolae’s moral decision precisely mirror those of the three Mrs. W’s from Wrinkle: Both groups are engaged in a fight against evil, and both levels of the fight are vital. A Swiftly Tilting Planet builds an intricate “For Want of A Nail” argument around the idea that each time people choose to act on either fear or love, to learn to forgive or to seek vengeance, literally leads the human race to the brink of nuclear annihilation.

This is heady stuff for a child, and frightening, but it also impresses you with the idea that you matter. Your choices are part of the universe. Obviously for L’Engle this choice had a theological element, but even here she uses a grab bag of references to classical mythology, Hinduism, Greek Orthodoxy, Celtic Christianity, and Hebrew Bible characters to get her points across. She creates a giant tapestry of references, along with her use of real science and science fiction, to imply the idea that universe is pretty big, and her characters are considerably smaller and doing the best they can. In Wrinkle, she makes a point of laying her cards on the table when Charles Wallace invokes Jesus in the fight against the Black Thing… but she also has several other characters rush in with their own examples of fighters, including the Buddha, Euclid, and Shakespeare. While she returns over and over to questions of “God”—and tends to put those questions into the Protestant context that reflected her own faith—she also populates her books with Indigenous people, Buddhists, Druids, atheists, people who’re secular and don’t think about it too much—and all of them have these choices in front of them. All of them are important.

As a writer, L’Engle taught me that there were no limits. A story that began in a warm New England home could travel all the way to a planet of furred, kind-hearted monsters who communicate through scent, or the antediluvian Middle East, or prehistoric Connecticut, or Antarctica. I could play with lasers, genies, time travel, griffons, or evil, pulsating brains, or even just a classic American road trip. It was all valid, and it could all make for a great story. I was valid, and my 12-year-old little self could make choices that could send huge ripples out into the universe.

Originally published in March 2018.

Leah Schnelbach wants to be Mrs. Who when she grows up. Come discuss hot Nephilim with her on Twitter!